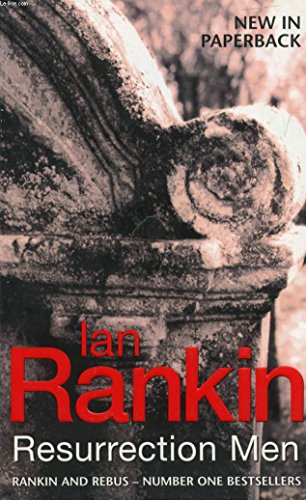

In that sense, the received idea of ‘literary fiction’ is put to real use in his work. A clearness about this idea of literary fiction has helped Rankin to write books which are its opposite: novels based on character, plot and under-described chunks of the real world. Nobody wants to define ‘literary fiction’ for fear of sounding stupid or philistine, but at the same time everybody knows what they mean by the term. So the Rebus books were born in a deliberate avoidance of the literary – or rather, of a certain idea of what the literary should be. My idea was: cop as good guy (Jekyll), villain as bad guy (Hyde).’ The result was Knots & Crosses, an attempt ‘to update Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde to 1980s Edinburgh. Dad’s reaction made me think about the kind of writer I wanted to be. Working-class working man against the system. So Rankin gave James Kelman’s first book to his father. He gave it to his father, who read it, ‘and went back to his bookshelf: James Bond, Where Eagles Dare’. * Rankin’s first work, The Flood, was an autobiographical novel ‘all about a teenage boy living in a Fife mining town and dreaming of escape to Edinburgh’. Rebus gets there just in time to save his daughter, though not without being shot – the first of the many woundings, beatings and physical mishaps which befall him in Rankin’s books.Ī new edition of the first three Rebus novels – Knots & Crosses, Hide & Seek, Tooth & Nail – comes with an informative short introduction by Rankin about how he came to write them. He dashes off to find her but she has already been abducted by the killer, an army buddy of Rebus’s who cracked during SAS training and has held a grudge against him ever since. That’s a rebus it’s also the name of Rebus’s daughter. professor at Edinburgh University calls Rebus to say that, as the author of Reader Exercises and Directed Exegetic Response, he has noticed that the names of the victims appear to make up a word: take the first letters of their Christian names and surnames and they spell out the word Samantha. It becomes clear that the killer has some personal connection to the detective. Then a message is delivered to Rebus’s home: For those who read between the times. The first few messages say There are clues everywhere.

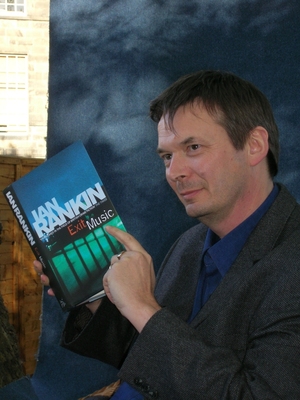

Rebus – 41-year-old drinker, ex-soldier, failed husband, absentee father, Christian, annual rereader of Crime and Punishment – begins receiving a series of cryptic notes. A series of local girls had been kidnapped and strangled. In 1987, Ian Rankin’s novel Knots & Crosses introduced us to a tough Edinburgh Detective Sergeant called John Rebus.

According to the OED, a ‘rebus’ is ‘an enigmatic representation of a name, word or phrase by figures, pictures, arrangement of letters etc, which suggest the syllables of which it is made up’.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)